How to Embrace Uncertainty in Foreign Policy

As Donald Rumsfeld so memorably explained to the world in 2003, there’s a lot of uncertainty in foreign policy. This is true for virtually every field of human endeavor. In physics, the hardest of “hard” sciences, the world appears to be fundamentally uncertain at the quantum level; particles behave with a randomness that scientists long thought was a violation of nature. In medicine, the sum of ignorance about the complexities of the human body towers over the meager sum of our collective understanding. In these fields, like so many others, we look to science and research to help us bring order to the seemingly infinite complexity.

When we ignore uncertainty in foreign policy, we invite disaster. Overconfidence seems to have been a damning factor in nearly every war the United States has since WWII — Vietnam, Korea, Iraq, Afghanistan, and more.

Managing uncertainty is a skill. It requires specialized techniques central to healthy decision-making. Chief Risk Officers have become a fixture in the business world. The intelligence world also understands this and makes uncertainty a central facet of every analyst's training. The Director of National Intelligence has issued clear directives on analytical tradecraft: “Analytic products should indicate and explain the basis for the uncertainties associated with major analytic judgments, specifically the likelihood of occurrence of an event or development, and the analyst's confidence in the basis for this judgment.”

Yet no similar emphasis exists at the State Department. Policymakers, in my experience, rarely create space for robust discussions about uncertainty.

This article is a primer on understanding how to manage uncertainty. I hope these ideas will encourage a deeper discussion about the process by which we craft foreign policy. Doing so could transform the way foreign policy is designed. As always, if you have different perspectives or anything to add, I’d love to hear from you.

How Should We Define Uncertainty?

There is a lot of diversity in the how people define uncertainty. The resulting confusion is a great reason for the foreign policy community to propagate its own official definitions to make sure we don’t talk past one another. I want to share my preferred definitions not to assert a “true” definition but rather to encourage shared understanding. Some of these definitions are borrowed from Douglas Hubbard’s excellent book How to Measure Anything, which is a great book for those who want to dive deeper on these topics.

Probability: the likelihood that an event will occur. For example, the probability of pulling an ace from a standard deck is once in every thirteen cards, or about 8%.

Uncertainty is a state of limited knowledge in which one cannot exactly describe the existing state or a future outcome. For example, the probability of rain tomorrow is uncertain, but the meteorologist estimates 80%.

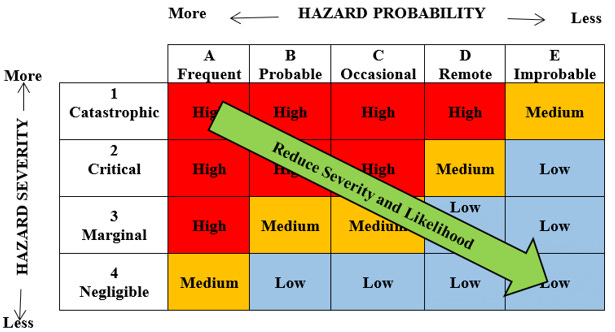

Risk is a state of uncertainty, where at least one possible outcome will lead to significant loss. It can be understood as the product of the probability of an event and the cost of the damage if the event occurs. For example, if I have to cancel my outdoor event tomorrow because of rain, I will lose approximately $10,000 in sales revenue. If there’s a 20% chance of rain, the risk is $2,000.

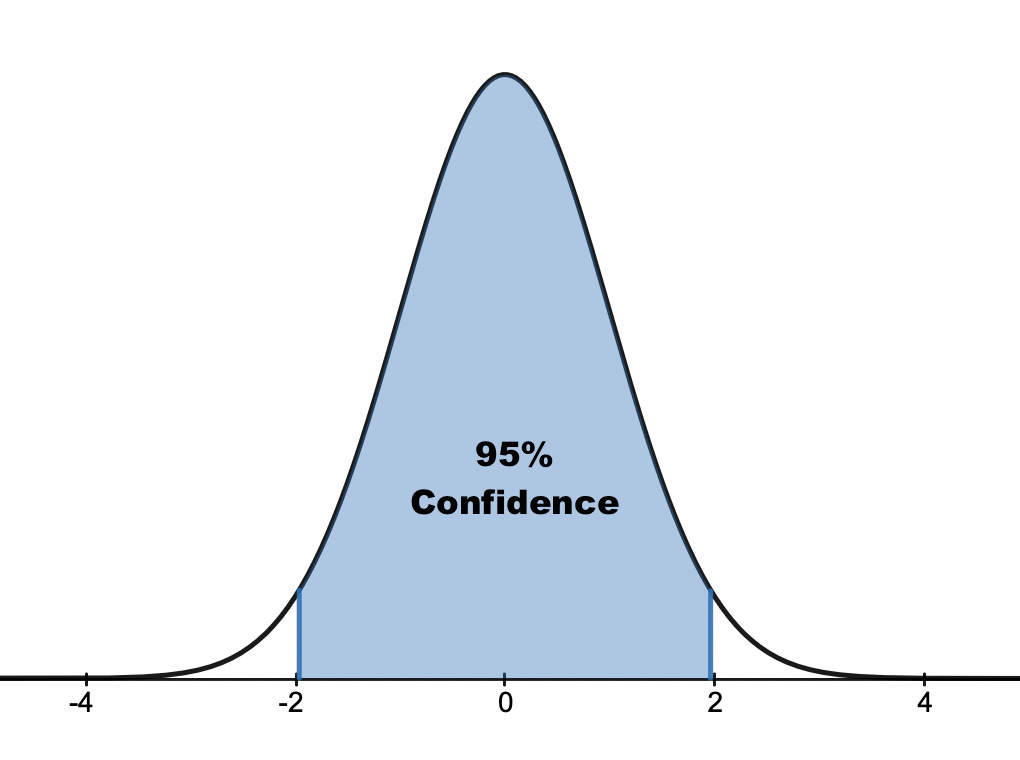

Confidence is the degree of certainty one holds in a measurement or forecast. For example, I have 100% confidence that my coin will land heads 50% of the time. Overconfidence, thus, is not simply predicting a tail and then witnessing a head – it occurs when one assigns too high of a probability of getting a head. For example, the gambler's fallacy might lead one to believe there’s a 75% probability of flipping a head after a miraculous series of 10 heads in a row, a classic cause of overconfidence.

A confidence interval sets statistical bounds on an estimated measurement or prediction, such as: I am 95% confident that between 10-20 people will attend my lecture tomorrow. These can also be described in certain circumstances as margins of error, such as in surveys of small groups that are intended to reveal the preferences of the entire population. Confidence intervals are helpful because they can be used to calculate one’s predictive precision over time.

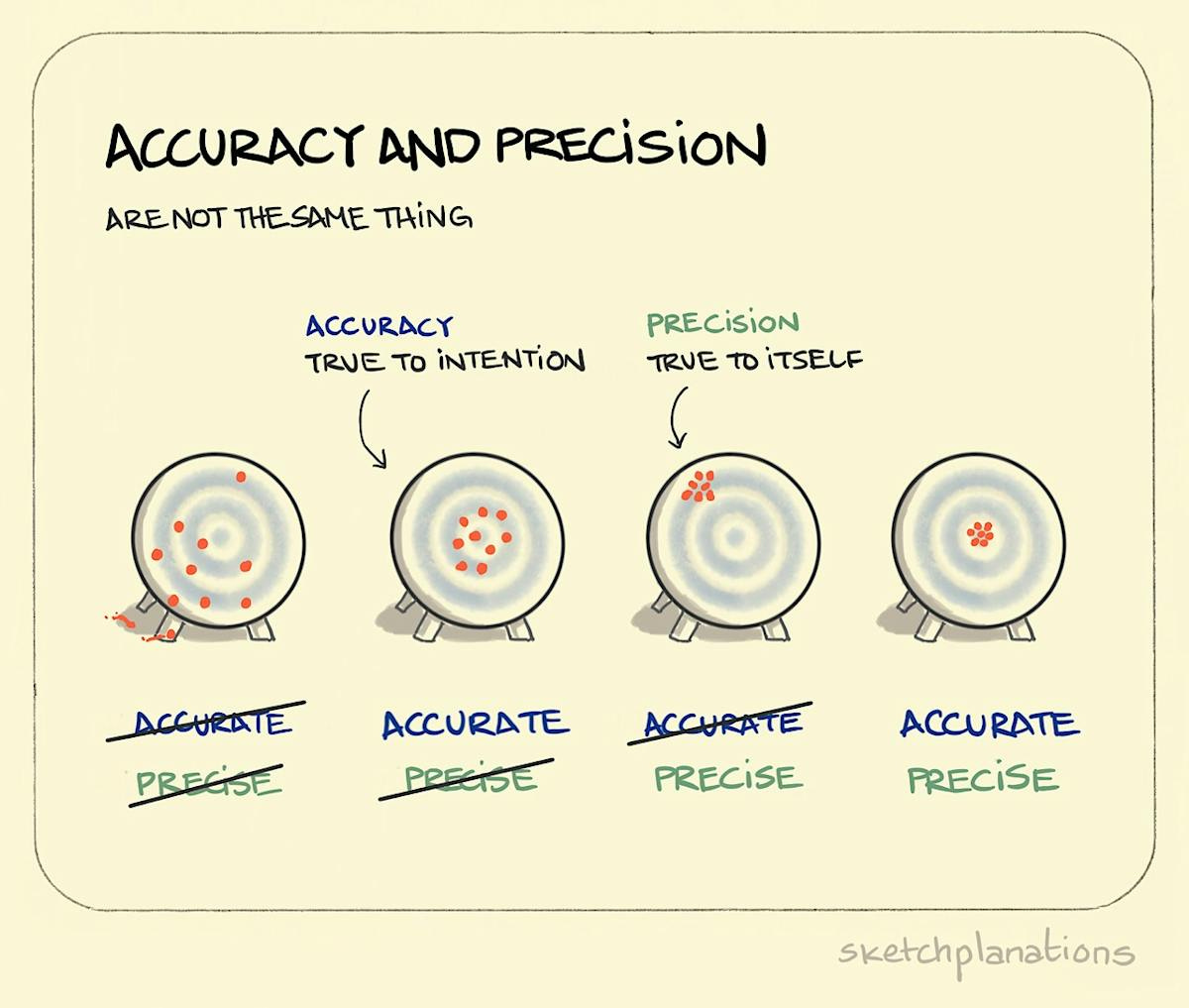

The accuracy of one’s predictions can be measured by how often one gets the right answer, or by how close to the right answer one tends to get.

Precision measures confidence intervals, not accuracy. In forecasting how many people will attend my lecture, a confidence interval from 0 to 100 is less precise than from 14 to 16. If the correct number turns out to be 15, both estimates will be accurate, but one more precise. One can measure average precision over time if many estimates are made.

Where does uncertainty appear?

An essential skill for policymakers is the ability to recognize uncertainty in every phase of the foreign policy process:

There is uncertainty in our ability to describe what is happening in the world. e.g. How many Russian troops are currently in Ukraine? How quickly is Ukraine replenishing its troops and materiale?

There is uncertainty in our ability to explain the world. e.g. Why is Putin so committed to the war in Ukraine? Why do the American people care about the war (or not)? How does US diplomacy shape the behavior of NATO allies?

There is uncertainty about the future. e.g. How long will the war in Ukraine last? How many people will be killed? What will a peace settlement between the two countries look like?

There is uncertainty in our ability to understand the likely effect of our policy options. e.g. What kind of weapons does Ukraine need to most effectively resist the Russian military? How can the United States minimize the risk of a nuclear response by Russia? Which diplomatic interventions will be most likely to isolate Russia from its allies, rather than push them closer together?

Notice from this list that some of these questions call for qualitative versus quantitative answers. That’s OK! Qualitative questions can often be asked in such a manner as to invite clear descriptions of uncertainty and confidence. There is evidence that doing so – and assigning quantitative probability and confidence to one’s answers – actually improves the quality of our analyses and predictions.

How to manage uncertainty?

Pinpointing uncertainty is hard enough. But how do we manage it in a chaotic world?

Today, most foreign policy decision-makers assess risks and opportunities using their instincts, making calculations only in the most informal sense, in their heads. Yet decades of research in cognitive science demonstrate that the human brain is actually quite poor at managing uncertainty and risk. The brain evolved to help us survive in a dangerous and wild world, reacting quickly and instinctually to threats like lions and snakes, not calculating probabilistic strategies in games like poker, let alone international relations.

Certain tools and techniques have proven superior to human judgment. My goal here is not to create a complete manual for how to use a variety of tools (maybe someday!), but rather to hypothesize about how different kinds of uncertainty invite different approaches.

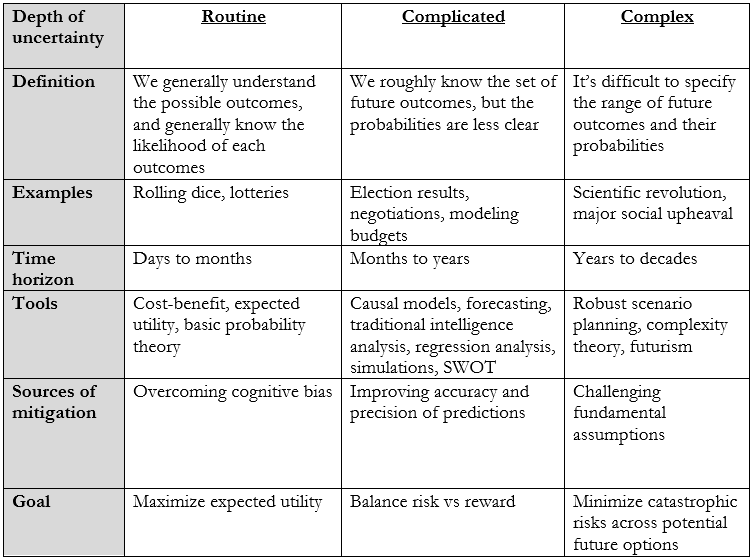

It is helpful to consider three categories of uncertainty: routine, complicated, and complex. These categories are not intended to be black and white. Rather, these are heuristics intended to improve the ability of foreign policy practitioners to manage the uncertainties inherent in their work.

Routine uncertainty

Routine uncertainty means that we know the set of possible outcomes and can reasonably estimate the likelihood of each outcome. Examples include predicting the outcome of rolling a six-sided die or guessing the winning in an election chosen by random lottery. Typically, we understand the mechanism causing the underlying uncertainty.

Routine uncertainty does not mean we can eliminate uncertainty, nor does it mean that uncertainty is necessarily low. Knowing a fair coin will land on heads exactly half the time means one can make carefully calculated “bets” on the future. Likewise, if a lottery ticket has exactly one in a million odds, the situation is nevertheless routine uncertainty.

Routine uncertainty is the simplest case for managing uncertainty and risk. One can carefully calculate probabilities and evaluate the risk associated with each outcome. The key challenge for decision-makers in such a setting is to avoid emotional decision-making and cognitive biases such as the sunk cost bias or the hot hand fallacy. Many techniques are available to help people limit cognitive biases.

Situations containing routine uncertainty in foreign policy are rather rare, but may crop up in administrative settings. If one faces such a situation, one ought to make a smart bet on the outcome with the highest likely reward while mitigating against potential losses. Calculating such “expected utility” should be rather straightforward. Instincts toward risk-aversion – the sort that is said to plague the State Department’s decision-making culture – must be combatted in such settings.

Complicated uncertainty

This sort of uncertainty is much more common. In situations of complicated uncertainty, one will generally know the likely outcomes, but have difficulty discerning the likelihood of any particular outcome. Imagine a deck of cards in which the dealer has cheated and removed many of the cards, so you cannot calculate the odds well.

Foreign policy examples might include picking the winner of an election, predicting voting results at the UN, or modeling an organization’s budgetary needs. Complicated uncertainty arises because there are many factors affecting an outcome, or an event is so rare that it is difficult to establish a baseline probability. We may know a particular event is possible – it occurs with relative frequency – but it’s hard to predict the timing. The time horizon for complicated uncertainty tends to be measured in months to a few years.

To manage uncertainty in a complicated setting, policymakers should consider reaching for structured analytical tools that help bring order to a complicated situation. The most effective technique for assigning probabilities is often to set a baseline probability by evaluating results from similar processes in the past. If one is assessing the probability of a civil war in the United States, one might evaluate how often other democratic states have descended into violence each year. Alternatively, the United States itself has been embroiled in civil war for 4 of its 248 years; a 1.5% chance of civil war per year is an excellent first guess without having to know anything about today’s political climate.

Unlike routine uncertainty, complicated uncertainty features a fuzzier understanding of the factors causing the underlying uncertainty. Policymakers might draw insight from academic research on their topic of interest, especially that which evaluates these underlying mechanisms and how they’ve operated in the past, such as the causes of successful peace agreements, countering violent extremism efforts, or the effects of a new trade agreement.

One might also use simulations – either narrative-based or more quantitative approaches – to help think through the factors and conditions that might lead to future outcomes. Forecasting tools (such as the superforecaster techniques popularized by the scholar Phil Tetlock) may be especially useful; they are proven to be more accurate than unstructured guessing. Expected utility modeling or SWOT analyses can clarify the strengths and weaknesses of different options. The intelligence community uses an approach called analysis of competing hypotheses in such settings.

When facing complicated uncertainty, policymakers need to slow down and avoid the impulse to shoot from the hip. A more conservative approach is required, one that considers best and worst-case scenarios, balances risk vs reward, and makes room in one's analysis for unexpected results. With longer time horizons and increased complexity, there is more possibility for so-called black swan events, which are those that are rare and unexpected but will have a profound impact on a system. Policymakers would be wise to aim for likely, preferred outcomes, yet still prepare for the worst.

Complex uncertainty

In environments of complex uncertainty, the situation will be so open-ended that the range of possible outcomes is largely unclear, rendering attempts to assign probabilities to different outcomes nearly impossible. Examples of challenges defined by complex uncertainty include planning an optimal democratization strategy or predicting the societal impact of the next technological breakthrough. Such situations often deal with time horizons measured in years or decades.

When confronting situations defined by complex uncertainty, the policymaker’s goal should be to identify a robust policy that works well across many outcomes rather than attempt to pick an ideal policy that only works under a narrow set of circumstances. Instead of betting on a particular outcome, a robust policy mitigates as many risks as possible and preserves room to maneuver across a broad range of possible futures. When facing complex uncertainty, overconfidence is particularly naive and dangerous; any assertion of a likely particular future outcome will almost certainly be wrong.

Robust scenario planning exercises can help policymakers challenge their implicit assumptions and stress test a range of theoretical shocks to the system. Brainstorming, futurism, and other creative approaches are useful.

Summary

Foreign policy is hard. Really hard. But when our policymakers ignore uncertainty in favor of instinct-driven assertions, they pass up opportunities to make it a little bit easier. Managing uncertainty should be a core skill for every aspiring foreign policy expert. The methods for doing so should be central in any curriculum for developing expertise, and be embedded in doctrine for diplomacy. The goal is not to be perfect – there is no such thing in an uncertain world. But the more we can reduce uncertainty and quantify the costs associated with our policy options, the better our national security will be.